When it comes to my relationship to the material world, I have perceived a clash between what I’ve been trained to value as a designer and what I feel is valuable to me as a person. For this to make better sense, I will paint two pictures from my own immediate, personal life – my childhood home and my grandmother’s home.

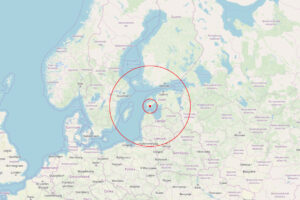

I was born in Kuressaare, a small town on the island of Saaremaa, into a country then called the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, part of the Soviet Union. The country regained its independence when I was 5 years old. This also meant that a communist planned economy was switched into a free market capitalist one, as fast as possible.

In my childhood home, my father was the interior-designer-in-charge. He was the one who brought home fashion magazines, read up on design and art history.

Looking back at my childhood home and my father’s passion for interior design now, years later, I sense in his vision the underlying urge to belong to the Western world as fast as possible. For our family to live in a space that we could see in American or British or Scandinavian interior design magazines. For a young man who is starting a family during the collapse of the Soviet Union, I can see how the interior of our home could have been so important, a way to affirm our own belonging in the world. To lift us out of our daily inferiority complex.

In the middle of a revolution for re-independence, after decades of occupation and cultural repression, the whole country was in chaos. People trying to find their way in a fresh and rampantly unstable capitalist economy. Despite the chaos, as a kid, I remember the optimism. It was almost like a high. A high from democracy, a high from all the choices – you could suddenly choose who to vote for, but with enough means, you could also choose a couch different from everyone else’s.

When there is such messiness and chaos prevailing in the broader society, it makes sense to focus on what you can control and build yourself, the insides of your home.

So what our home looked like, it feels almost like a caricature now – imitating interiors from Western design books. Replicas of rooms where we imagined people living prosperous lives in democratic societies. I loved that house but the more time passes, I see how it was, amongst other things, a sign of its times.

We had a kitchen with the maximum amount of clean surfaces. They were meant to be kept empty, nothing put on them, just like you see in architecture photos. No knick-knack or little tablecloths or cutesy things. Things like fridge magnets were unthinkable. The shiny surfaces demanded constant cleaning, as well as the black tile floors which were really unforgiving if you have children and pets with muddy paws running around. Looking back, it feels quite exhausting how much care it took, the upkeep of that minimalist interior.

At the same time, I often hung out in my grandmother’s place. All of her things were covered with something. Her room was covered with floral wallpaper. When the sun was out, I could see the cheap plastic-y material shimmer on her walls. Every flat surface was covered with a crocheted some-thing. A tablecloth on every shelf, one on a big clock, one on her washing machine. All of the floor was covered with different carpets.

I’ve seen her cover her bed with the same leaf-patterned fabric for the past 30 years. Fake flowers on the cupboards, mixed together with living plants. Little miniature souvenirs from the travels of her kids or grandkids.

She has 6 years of school education, she was brought up during the war on a farm, has never travelled outside of the former Soviet Union and never not lived on that island. She is 85 years old, of which she has been sewing and knitting almost daily for the past 70+ years.

At our modern home, there was a fireplace that was a huge cube made from beautiful locally sourced dolomite stone. The few small carpets we had, were ordered from a crafts woman, loomed by hand with grayscale geometric patterns. Furniture was ordered from local carpenters as much as possible, but the designs were often taken from design magazines or books. The idea was to invest in long-lasting things, because this was it, the plan was to never need another fireplace, another carpet or any other kitchen furniture.

My grandmother’s floors are almost entirely filled with carpets, you barely notice there is a wood floor underneath. The carpets are definitely not handmade but in synthetic material, from this time I think in the 90s when they became cheap enough for her to buy. Now she could afford these flawless store-bought carpets that are easier to clean and never wear out.

Once she almost threw away an old bed cover that her mother – my great-grandmother – had loomed herself in a yellow and white pattern. It is uneven on the edges, but such a nice, soft and fluid material. My great-grandmother had grown the linen herself, picked it herself, gone through that whole process of turning a plant into a thread, then dying it, then looming this fabric… Mind-blowing to me. I couldn’t believe her – How could you have thrown this away?

But she enjoys the fabrics that don’t wrinkle. She has three layers of synthetic curtains that sparkle with static electricity in the winter and she doesn’t mind.

The stairs in our house looked like they were grey stones floating in thin air, without a handrail. Once at night my father fell on the stairs, through three floors, breaking one of the stone plates with his back. Luckily we can have a laugh over it now – what a risk to take for aesthetics!

We had fake Charlotte Perriand chairs with cowhide seats in the sauna dressing room, which you had to cover with a large towel because who wants to sit on hairy leather after sweating in the sauna?

Next to those chairs, there was a tiny pool made of turquoise mosaic tiles. There was never any water in that pool, just a dry blue hole in the floor. Funny to remember now that I’ve seen other houses like this in my childhood, that had these dry pools in their basement. Felt like the pool-enthusiasm faded half way through building. Or maybe we all realized that in the capitalist economy, you need to pay for all that warm water.

Many of my friends also lived in similar houses that we now know, are too big. Too big to afford to heat, too big to clean. But our parents got the land for their houses during the privatization of the 90s often through lottery, and the building material was so cheap (often just stolen) it didn’t matter, so why not go big? Nobody had the experience of paying for electricity either, so it was hard to really grasp what that electrical floor heating would end up costing…

I remember the house being cold. Not as a sad metaphor, but literally, with cold stone floors and lots of glass, no matter how much effort was put into heating it, it was still chilly inside. In winter mornings, there was a race to the shower because that was the only warm place.

All of this together, I realize how absurd and dysfunctional our house was. Even though I had the best time living there – it was fun for a kid to live in this perpetually unfinished, never-ending project that was powered by raw ambition and optimism.

Aesthetics were by far more important than function, truly an ironic joke on the modernist design that the house was inspired by. Or rather, the function of the modernist aesthetics lay in holding up the dream of Western capitalist ideals.

I guess I’m telling this simplified story as an example of how I see an ideology express itself through people’s taste. In this case I can see Western democracy, free movement, all sorts of individual freedoms and rights we didn’t have before, and capitalism. That is roughly what I feel seeping through this house when I think of it. And I’m haunted by the memory of this dry pool in the basement, how the lure of abstract ideologies might visualize in an absurd image like that. My father gave me books about contemporary art for Christmas. And as I was still living on that island, it’s not like I had ever been to an exhibition. His ambition in this sort of fast learning is clearly the reason why I could get educated in Western design schools, he gave me the tools to become a part of this discourse.

After having gone through design education in Amsterdam and Stockholm, I’ve been haunted by this division of taste I have inherited from my father and the taste of my grandmother. While I’ve enjoyed my time in that metaphoric “father’s house”, I have felt quite helpless navigating my grantmother’s aesthetics.

I’m haunted by the way my grandmother’s craft and care knowledge has been largely discarded and financially worthless in both regimes of her lifetime, be it communist or capitalist. The way her taste in cheap useless things is considered tacky. I have not seen her side of my visual culture represented anywhere during my design education. So during my master project I have been spending time to fill that gap for myself.

This project looks into her decorated universe and takes some notes on how she operates. I will do this through the lense of different local markets as that is where she mostly sources her material world, that is where I see women like her exchanging their visual references.