*

It is fair to say that my grandmother knits non-stop. She says she can’t watch TV without knitting anymore, she falls asleep.

I remember getting a bit upset with her for selling her knits so cheap, practically for free. Now I see I was the fool, thinking money is any motivation for her, she just likes to keep busy, to make things.

There are tons of crochet tablecloths around her place, covering almost every surface, covering the tables, the shelves, the TV, also the washing machine. It is obvious she hasn’t put them there for practical reasons and the fact that they are such a challenge to my “educated taste,” is something I think needs looking into.

*

I am fascinated by the repetitive nature of needlework. I see so many handmade table covers sold for nothing on osta.ee, the Estonian online “ebay”. What is behind the urge to keep on producing them? What kind of mental space would I enter when working on handicraft? What kind of pleasure would my brain get, if I kept repeating a formula through my hands like that?

There is a formula you must memorize, to pour out that pattern flow. A different formula produces a different pattern. Once you stick to a formula, you can let go of “thinking” further about it.

*

This is what my grandmother has said about her knitting time – that she enjoys the “not thinking” while knitting. It seemed strange to me, feels like reading or memorizing a pattern IS thinking, but maybe not to a master-level knitter.

*

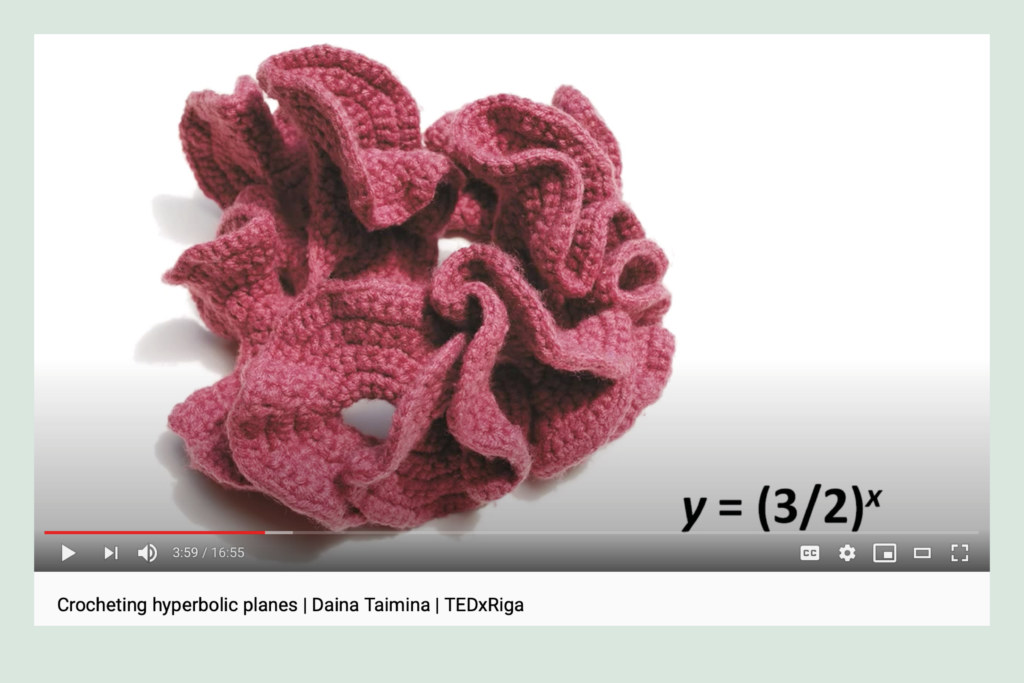

Needlework can look very mathematical to me. Even though a crochet tablecloth is almost the diametrical opposite of the Western idea of mathematics. The math taught at school is communicated through abstract conventions – numbers, formulas, graphs – very high forms of alienation from any practical, material world.

I have heard it many times that someone is convinced that he or she is “bad at maths” – maybe it is simply the communication of math, the abstracted symbol system that doesn’t suit them?

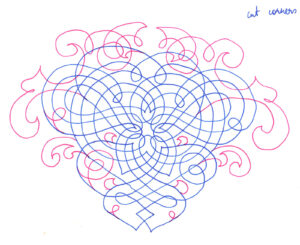

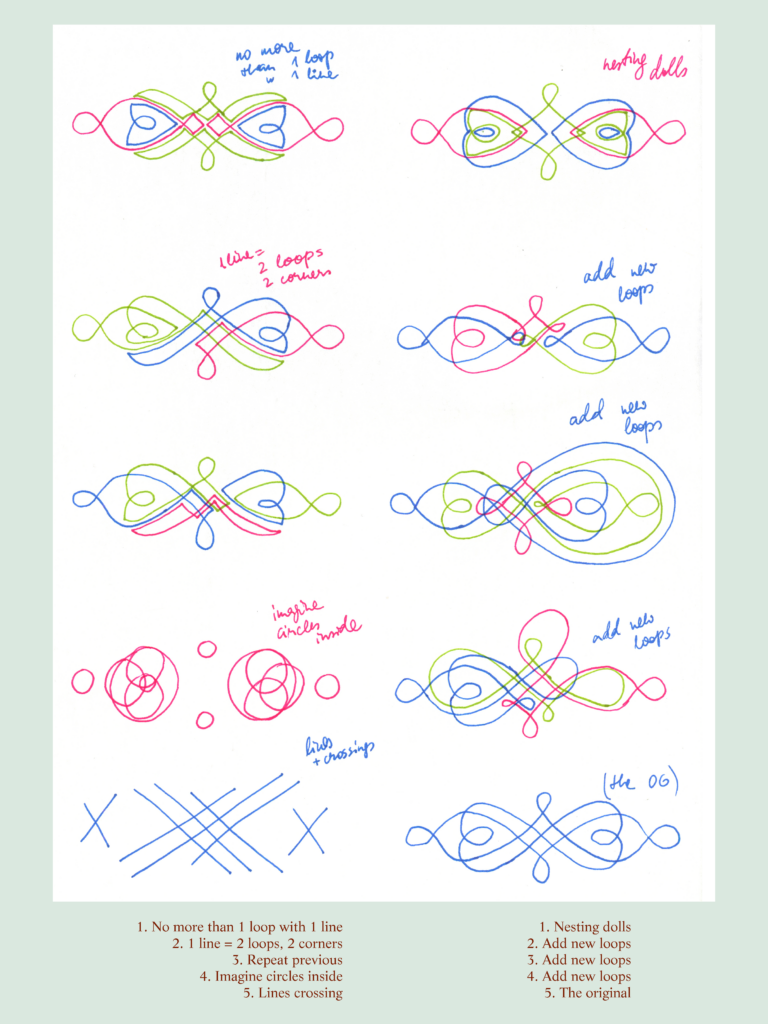

I explored ways of using formulaic repetitions to create ornaments. Disguising mathematical formulas into lush graphics was the dream I was chasing.

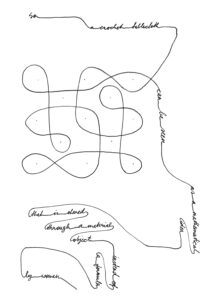

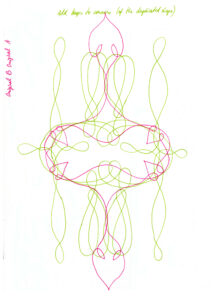

I copied the structure of ornaments from different craft books, drew them with one line and modified them by giving myself some arbitrary commands. These experiments were very literal with the “mathematics”, trying to program ornaments.

It became like a game where I gave myself scripts to alter the shapes I had in front of me. I gave new scripts or commands as I went along.

These exercises helped me to better understand the logics

of the ornaments I copied.

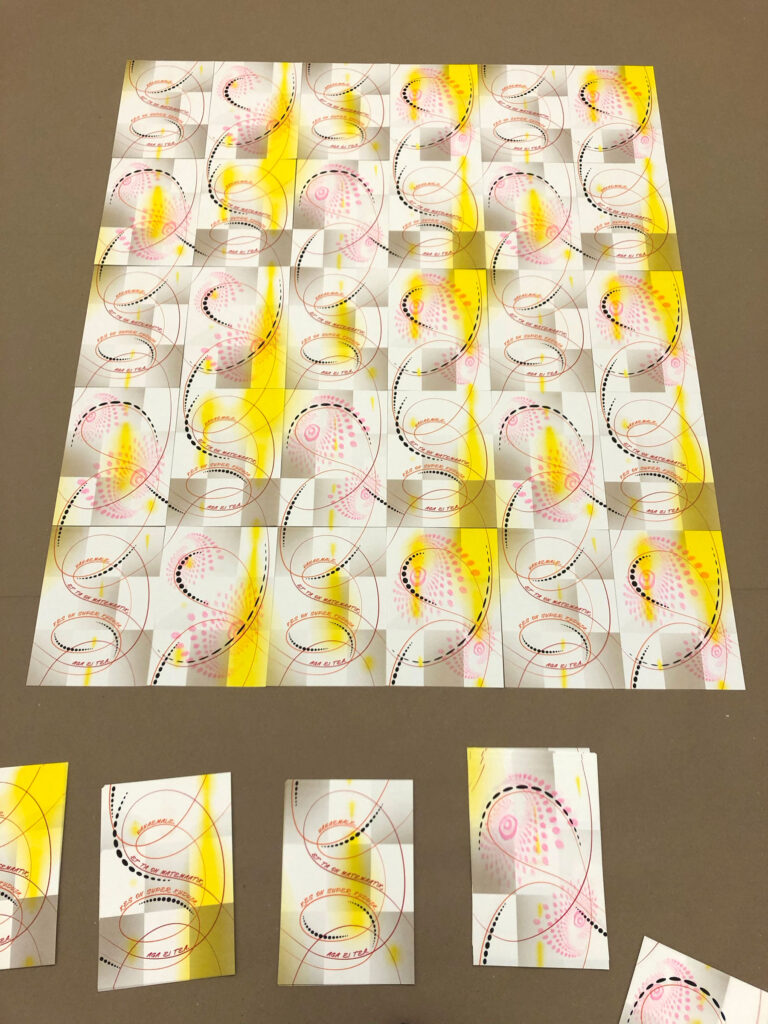

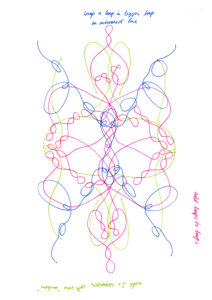

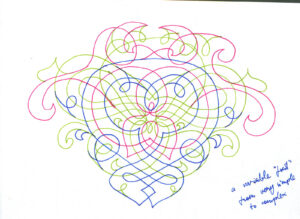

I took a break from these excercises but came back to them next year when I wanted to construct pattern repetitions. For this I started using a similar method of superimposing one-line shapes and making them dance on one surface.

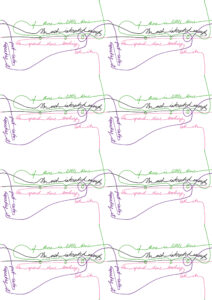

I found that I like to write text in this way that gives sentences shape and rhythm. Without the text, I was lost in what shapes to draw. And I think the text also helps the viewer to follow the line more intimately, to get into the movement of a pattern or ornament.

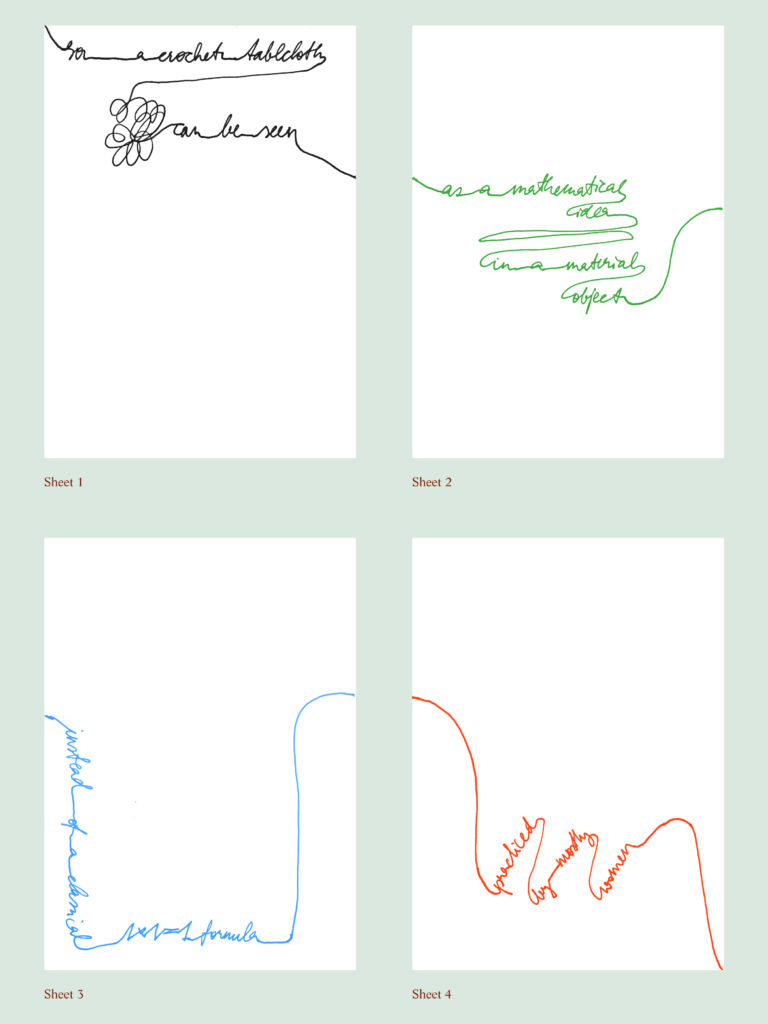

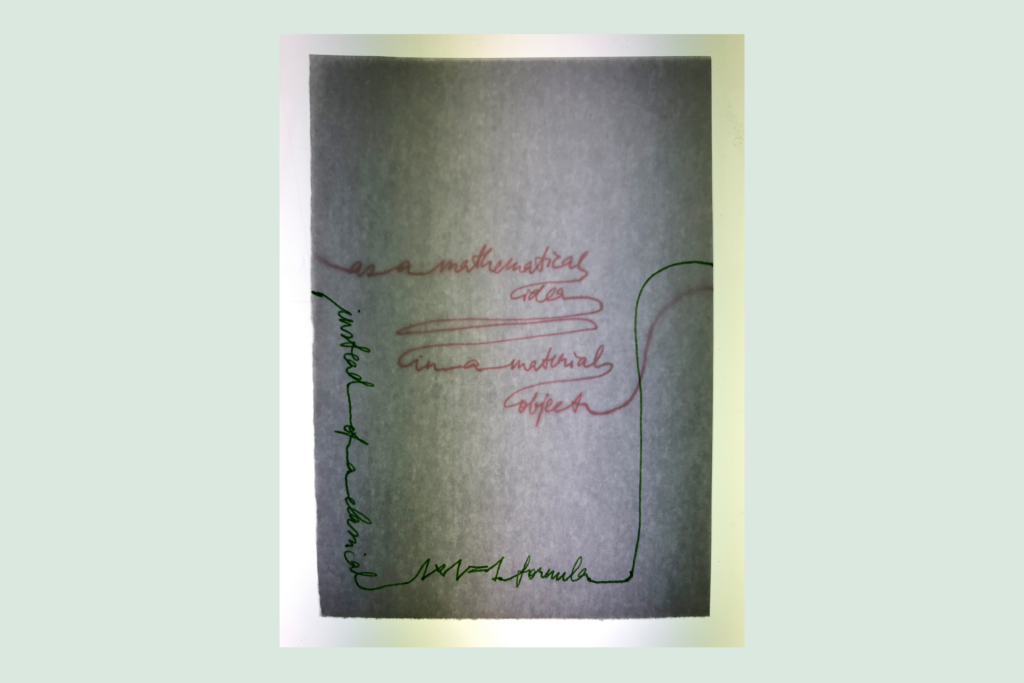

I wrote a thought or sentence on multiple sheets of paper so the line connects from one sheet to another. Also, the line ends on the last sheet and starts again from the first sheet. This creates a looping effect.

I used a light table so the text wouldn’t overlap.

The patterns are made out of one continous line. This I found to be similar to the idea of an ‘interlace,’ a concept from decorative arts:

“the arrengements of crisscrossing bands. Assumed to come from knots and other forms of decorative ropework.“

(The Language of Ornament, James Trilling)

I recognize a sensation when making these interlaced line patterns from Trilling’s descriptions of the historically ‘magical’ powers of interlace and knots:

“Knots have a long-established place in the lore of supernatural attack and defence. A curse or a spell was often ‘secured’ with a knot, and could only be disarmed by physically untying it. It is very likely that over and above its decorative value, interlace was magically protective, or apotropaic (from the Greek word for deflection). As a permanent ‘knot,’ it defied the evil-doer to untie it mentally by tracing out its windings and crossings, as one might solve a difficult maze. Since the more complex the knot, the more protection it would have offered, superstition was a powerful incentive to create ever more intricate patterns.“

(The Language of Ornament, James Trilling)

I haven’t counted superstition as one of my motivators, but I share the fascination with these surfaces that are impossible for my brain to ‘untie’.

I aim for that level of complexity with my patterns that are difficult for my brain to solve at a quick glance, hard to ‘see through’, but at the same time seductive to the senses because of their symmetry and flow.

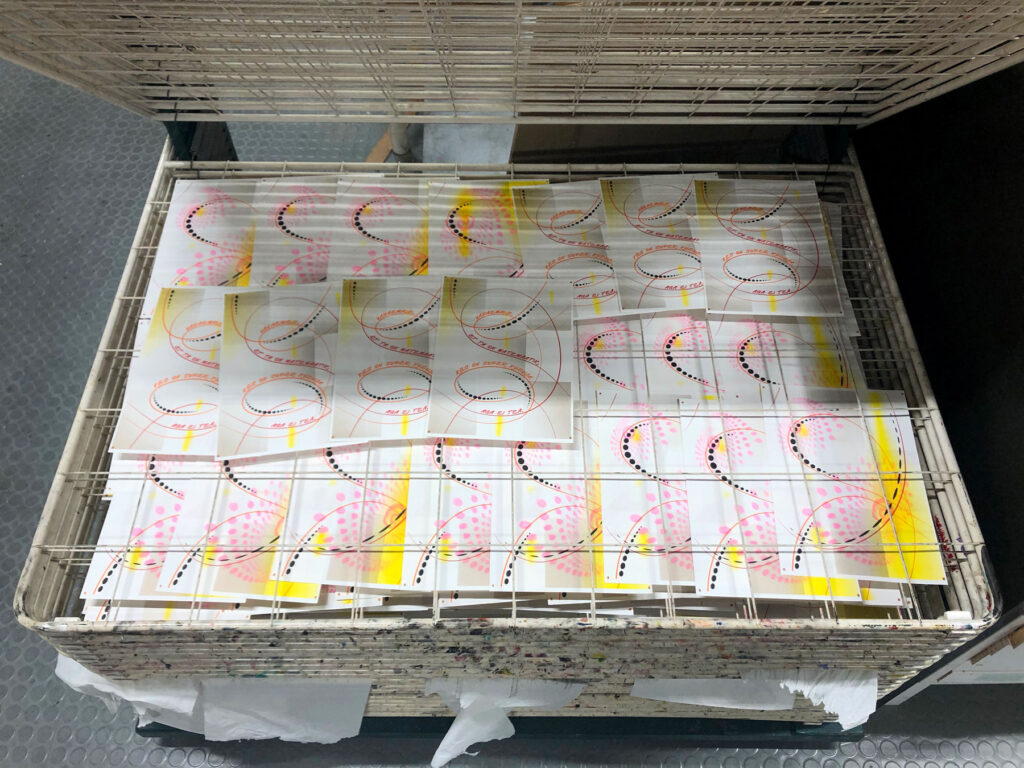

I was having fun with this method of creating an interlace pattern. But looking back at my “market-research”, I wanted to create more layered and lush patterns, so I start adding more visuals to my text-based strucure.

I find it hard to work on multiple layers at the same time. There are too many loose ends if I can go back and edit any part of the pattern whenever I want. To get rid of this anxiety, I started printing it out layer by layer. Once it’s printed, I can’t change it. This restriction gives me the freedom to think only one layer at a time. The layer is finished when I am excited enough to print it.

I print on the risograph printer because it prints one color at a time. Every new pattern layer in my digital file is a new color layer for the printer. Each layer has its own unique function to create movement, depth and atmosphere to the pattern.

I think of this way of designing-while-producing “the patchwork method”: as I’ve heard a myth that the craft of patchwork comes from the need to work in little units of time. When women didn’t have big chunks of time to work on ‘a project,’ they used the little bits of free time here and there. So you sew a patch when you happen to find time, without a fully preconveived design.